The story of the societal impact caused by Upton Sinclair’s 1905 novel, The Jungle, is a strange and fascinating one. With almost journalistic accuracy, the novel viscerally tells the fictional story of a young Lithuanian immigrant worker in Chicago’s factories at the beginning of the twentieth century. He, his wife, and his friends are repeatedly conned and taken advantage of by their landlord and bosses, who subject them to systemic abuses, harsh working conditions, and unlivable wages partially because of their immigrant status and low socioeconomic standing. The novel, which sold tens of thousands of copies within a year, is unabashedly supportive of workers’ unions and labor and immigrant rights. However, these political messages were not what readers took from Sinclair’s book. Instead, since the time it was published, The Jungle has primarily been famous for its depictions of the unsanitary conditions of the meat packing industry. Why did nineteenth century Americans tend to ignore the suffering of the immigrant working class? The public reaction to Sinclair’s portrayal of the plight of working class immigrants appears to have been a symptom of the broader political climate of the time, stemming, in large part, from one pivotal event in 1886. This event was the Haymarket affair, one of the most violent events of the nineteenth century labor movement, which created mass hysteria against immigrants and workers that was successfully harnessed by factory owners and businessmen to drive more radical elements of the labor movement to the fringes.

During the late nineteenth century, the United States experienced an unprecedented surge in industrial development – one that benefitted enterprising business owners at the direct expense of poor, mostly immigrant, workers. As demand grew, industry became increasingly reliant on “unskilled” labor in factories, refineries, mines and storehouses. These jobs were often some of the only jobs available to the urban poor, many of whom were first- and second-generation immigrants with limited knowledge of the English language (VandeCreek). Most came to the United States without much money, and were compelled to work unskilled jobs for low wages in order to survive, while factory owners enjoyed massive profits from their work. Historian Drew VandeCreek discusses this inequity in his article “Labor in Gilded Age Illinois,” explaining how workers in the late 1800s frequently worked ten or twelve hour shifts in unsafe conditions for poor wages. Garment workers in the late 1800s, for example, worked in sweatshops for between 60 and 84 hours a week, making as little as three dollars a week (equivalent to about $90 in 2024 – less than a sixth of what they would make if they were paid today’s federal minimum wage) (Layson and Fink). Many workers were also required to live in cramped company housing, and some were paid only in “company scrips,” a form of currency that could be used to buy household goods at company-owned stores, but was worthless outside of the company town (VandeCreek). In many cases, contractors actively relied on their ability to exploit immigrant laborers, some of whom were “imported en masse,” to act as cheap labor (Zinn 256). Thus, immigrants, even more so than American-born lower-class workers, were exploited by scions of industry to fuel American industrial development.

As a result of the exploitation they faced, many workers began to form workers’ unions, which attempted to organize labor strikes in an effort to leverage better wages, hours, and safety precautions. Unions, which were composed of a significant number of immigrant workers, were an integral part of the developing labor movement. Labor historian, Bruce Nelson, explains that, by the 1880s, there were generally two types of labor groups. On the one hand, those considered to be more radical, like the Central Labor Union (“CLU”), openly embraced socialist or anarchist views popular in Germany and Eastern Europe, and argued that workers should take ownership of factories and other means of production. Anarchist elements of the movement often argued for the use of force in achieving these goals. On the other hand, comparatively more moderate groups like the Knights of Labor still advocated for sweeping workers’ rights reforms, but did not adopt socialist or anarchist positions, and instead sought to bargain with factory owners. Yet the Knights of Labor were notable in their own right for opening their union to all people, regardless of nationality or whether they worked in skilled or unskilled positions (Nelson 2). In analyzing several labor protests leading up to the Haymarket affair, Nelson describes two Chicago protests – one organized by the Knights of Labor at the Cavalry Armory, and the other, a protest by the CLU in Market Square. The Knights of Labor protest, a relatively calm, indoor event with speeches by Protestant ministers, was mostly attended by Irish immigrants and American-born workers, with a minority coming from mainland Europe. In contrast, the CLU demonstration, an energetic, outdoor event with speeches by prominent labor movement figures, was attended by a diverse group of German, Czech, Polish, and other Eastern European workers. On the CLU’s protest, the Chicago Tribune wrote: “The marchers were mostly communistic Germans, Bohemians and Poles. There was scarcely an American, Canadian, Irishman, Scandinavian or Scotchman among them.” (Tribune qtd. in Nelson 2) This description is illustrative of the distrust and division that middle class Americans felt towards more recent immigrants, many of whom were coming from Eastern Europe. Even before the Haymarket affair, certain groups of immigrants like Germans and Poles were considered to hold inherently dangerous ideas, and their involvement in labor unions was used to discredit parts of the labor movement as “communistic” (Nelson 2). At the same time, the massive influx of immigrants during the latter half of the nineteenth century meant that there were more people than jobs, leaving many immigrants unable to find work. In his book, A People’s History of the United States, historian Howard Zinn notes how these conditions, coupled with the other difficulties faced by immigrants, caused some immigrants to be used by labor bosses as strikebreakers – replacement workers hired during a strike. (267) Thus, while many immigrants were active in the labor movement during the late 1800s, many others were also used as pawns to oppose and undermine this same movement for worker’s rights.

Among the demands labor unions and workers made to employers, the right to an eight-hour workday was the most prevalent. In 1876, the U.S. Supreme Court had recognized the validity of a federal law stating that “eight hours shall constitute a day’s work for all laborers, workmen, and mechanics employed by or on behalf of the government of the United States” (United States v. Martin). Since workers who were not employed by the government were still often required to work ten to twelve hours a day, unions sought the same eight-hour workday for non-government workers. By early 1886, they began to come together with the goal, described by Albert Parsons, a prominent organizer of CLU protests, “to see that on May 1 the eight-hour system was adopted for all laboring people”(qtd. in Nelson 2). In response to the demand for an eight-hour workday, employers, echoing fears expressed in the newspapers of the day, argued that the movement’s demands were “absurd”, and would “ruin industry” by causing factories to lose hundreds of hours of labor (Lerner et al.). Interestingly, while capitalist economists who wrote on the subject recognized that working fewer hours would significantly benefit workers, they retorted that reducing hours by even a small amount would also have potentially detrimental effects on the economy (“The Eight-Hour Movement”). Business owners considered profit and the growth of the economy to be more immediately important than improving the conditions of lower-class laborers. As a result, they continued to reject unions’ demands for an eight-hour workday, leading to a string of significant labor protests that culminated in a national tragedy during the Spring of 1886.

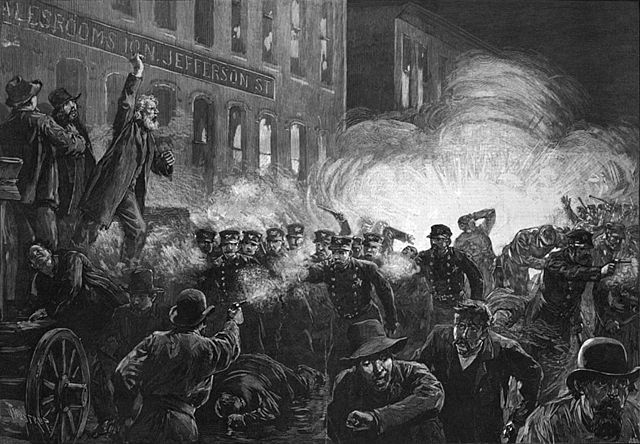

By May of 1886, the “Great Upheaval,” as the series of labor protests and strikes supporting the eight-hour movement became known, was reaching its climax. On the first of the month, a coalition of workers’ unions around the country held a mass strike in support of the eight-hour day, resulting in nationwide protests supporting the strikes. (Riggs) Two days later, a large group of striking workers in Chicago marched on the McCormick Harvesting Machine factory to prevent strikebreakers from entering the factory. The confrontation turned violent when police officers arrived to break up the protest, firing on the crowd of demonstrators and killing two (Parrish). This violence from the police incensed the strikers and movement leaders, who immediately organized a protest in response to the killings and in further support of workers’ rights for the next day, May 4th, 1886, at Haymarket Square. For most of its duration, the May 4th rally was nonviolent. However, when police attempted to dissolve the assembly during an especially fiery speech by labor activist and pastor, Samuel Fielden, an unidentified protester threw a bomb, killing seven police officers in the initial blast, and injuring an additional 60 officers. While the exact number of protesters killed or injured by the police following the explosion is unknown, it is believed that between four and ten protesters died, with an estimated 200 more injured (Riggs).

Although the police had no information about the identity of the person who threw the bomb, they almost immediately arrested eight leaders of Chicago labor and anarchist movements. The two labor activists who organized the Market Square protest, August Spies and Albert Parsons, were arrested. Only days before, the Chicago Mail wrote an article about them, urging the public to “keep them in view. Hold them personally responsible for any trouble that occurs. Make an example of them if trouble occurs” (qtd in Lerner et al). Samuel Fielden, who was speaking when the bomb was thrown, was arrested, as were five others, Michael Schwab, Adolph Fischer, George Engel, Oscar Neebe, and Louis Lingg. Of the accused – the Haymarket anarchists – all but Parsons and Fielden were German immigrants (Roediger and Rosemont 18)

News of the Haymarket bombing and the arrest of the eight Haymarket anarchists quickly spread around the nation, and with it, a sudden growth in xenophobia and anti-immigrant sentiment. Americans had long associated certain demographics of immigrants, specifically those from Eastern Europe, with socialism, communism and anarchism (Roediger and Rosemont 205). The Haymarket bombing, and specifically the fact that it was allegedly committed by a group of mostly German anarchists, confirmed many of the American public’s latent fears about the dangers these immigrants posed to the country. A New York Times article written three days after the bombing stated, “The Anarchists, as a rule, hail from Russia, Poland, Hungary and Bohemia. Nine-tenths of the Socialists here are Slavs, or a mixture of the Slavonic and Teutonic race” (‘Anarchists Cowed’). Police immediately cracked down on Eastern European neighborhoods, believing the inhabitants to be dangerous communists. Almost immediately after the arrest of Haymarket eight, policemen and privately hired Pinkerton agents in Chicago began to raid the homes of suspected anarchists without warrants. Describing the police activity, the New York Times reported: “There is hardly an Anarchist in the city who is not in a tremor for fear of a domiciliary visit…Search warrants are no longer considered necessary, and suspicious houses are being ransacked at all hours of the day and night.” (‘Anarchists Cowed’)

The trial of the Haymarket anarchists took place in November of 1886, roughly six months after the bombing (Gottesman and Maxwell). Since there was little or no proof of their direct involvement in the bombing – five of the men had not even been present at the rally when the bomb was thrown – prosecutors relied almost exclusively on the eight men’s words and writings in the days and weeks before the bombing to construct a case against them (Gottesman and Maxwell). The state’s case against the Haymarket anarchists, who were charged with conspiracy to commit murder, was that they were responsible for the bomb being thrown by indirectly encouraging individuals to commit violence (deMille 546). To establish their guilt, it was necessary to frame their speeches and writings as “inimical to the interests of the state…dangerous to the interests of the wealthy who controlled the state, if not necessarily the state itself” (Parrish). The implication that the state was prosecuting the Haymarket anarchists not for any direct actions they took but for their beliefs, was made explicit in court. Julius S. Grinnell, the state prosecutor for the trial, made fiery statements to the court, proclaiming that “anarchy is on trial,” stating that the Haymarket anarchists “were no more guilty than the thousands who follow them.” He implored the jury to “convict these men, make examples of them” in order to “save our institutions, our society.” (Grinnell qtd. in Parrish) Through the case against them, the state wanted to make an example of an ideological movement it believed to be antithetical to capitalist interests by prosecuting the movement’s leaders for a severe crime. It succeeded. A jury found all eight men guilty of conspiracy to commit murder, and on November 11th, 1887, Spies, Parsons, Engel and Fischer were hanged. Lingg killed himself shortly before his execution (Lerner et al.).

Following the trial, the events of the Haymarket affair continued to be used to vilify immigrants and silence more radical elements of the labor movement. Some, like Italian criminologist and eugenicist Cesare Lombroso, attempted to pathologize the beliefs of the Haymarket anarchists. To Lombroso, explicitly violent anarchism was not a result of an individual’s beliefs, but their “facial asymmetry, cranial deformities, skin discoloration, anomalies of the ears and nose, and the like” (Avrich 428). In his book, The Haymarket Tragedy, Paul Avrich notes how this focus on the physiognomy of a violent anarchist, though repeatedly proven incorrect, was still parroted by many newspapers and journals at the time, replacing the broad fear of anarchism as an ideology with the fear of a type of person. (429) Moreover, as a result of personal prejudices reinforced by news reports and political cartoons of the day, Americans perceived a disproportionate amount of these dangerous anarchists as coming from Eastern Europe. This belief became even stronger after the Haymarket affair (Roediger and Rosemont 205).

Even some better-off European immigrants faced prejudice that undermined their authority following the Haymarket affair. John P. Altgeld, a German-born man who served as governor of Illinois from 1893 to 1897, was vilified based on his German heritage after pardoning the three surviving Haymarket anarchists, because he believed, after reviewing the evidence, that they had been unfairly convicted. Following the pardon in 1893, the Chicago Tribune remarked that Altgeld lacked “a drop of true American blood in his veins. He does not reason like an American, does not feel like one, and consequently does not behave like one” (qtd. in Sampson). People did not consider Altgeld’s reasons for pardoning the anarchists. Instead, he was viewed as having sided with them – something that people said he would only do on account of his nationality (Sampson).

The widespread fear of anarchism and immigrants eventually reached the federal government. Avrich describes several bills proposed in the House of Representatives with the intent of either deporting anarchists with an immigrant background or keeping “avowed anarchists” out of the Country (430). In 1888, a bill calling for the deportation of all immigrants deemed “dangerous” was proposed, but failed to pass. In 1889, a similar bill calling for all incoming migrants with anarchist or socialist views to be denied entry to America was proposed, but similarly failed to pass. Similar bills were proposed until 14 years later, when in 1903, a bill preventing anarchists from immigrating to the U.S. was passed into law (Avrich 430). Following the Haymarket affair, anarchism became viewed as a uniquely foreign, un-American threat. The Haymarket affair was used to fuel American xenophobia, which was in turn used to silence labor movements.

Because so many workers were immigrants, unions were similarly composed of a large number of immigrants, who were now considered by a significant swath of the U.S. population to be a violent, anarchical threat to America. This sentiment was used by factory owners and politicians to erode the credibility of the early labor movement. As Avrich describes it, “the hysteria aroused by the bombthrowing…was directed against workers of every ideology and affiliation” (429). Americans became increasingly afraid of violence coming from labor movements, which was compounded by the country’s new-found paranoia of violence from immigrants. Violence, labor unions and immigrants became inextricably linked in the American consciousness for the next several decades. Hartmut Keil discusses this effect in his article, “The Impact of Haymarket on German-American Radicalism”:

Seizing the opportunity of the fatal bomb-throwing and immediately taking the initiative, the established part of Chicago society mercilessly exploited Haymarket for its own purposes. As a symbolic event, then, Haymarket helped…to delimit the acceptable parameters of legitimate political action and behavior, and thereby to influence the future perceptions and actions of individuals and groups. (Keil, 17)

After the Haymarket affair, the acceptable options for labor movements became far more constricted, as captains of industry harnessed Americans’ fear of violence and anarchism to limit the effectiveness of unions. Keil also notes how factory bosses began blacklisting union members from work, which drastically reduced union membership, and consequently, the ability of workers to advocate for their own rights in a meaningful way (22).

In the span of just a few years, the labor movement was reduced to a shadow of what it once had been; the eight-hour movement was disrupted, and little-to-no progress towards mainstream adoption of the eight-hour day would be made for several years (Avrich 454). Through manipulation by factory owners and other members of the upper-class, the general public either became wary of, or were forced to, abandon the labor movement. Even the Knights of Labor – a politically moderate organization compared to many other early union groups – was essentially destroyed following the Haymarket bombing. What remained of the labor movement was forced to adapt to a climate hostile to many of its prior beliefs. In his article, Keil wonders, “…was not another legacy lost in the wake of Haymarket?” A legacy was indeed lost. The mainstream labor movement that emerged in the years following the Haymarket affair abandoned the politics and history of the movement that came before it (Keil 25). Even Altgeld’s 1893 pardon of the three surviving anarchists, where he determined that the trial had been biased, is but a footnote compared to the rest of what occurred following the bombing (Sampson). By the time of the pardon, the damage had already been done. The Haymarket affair had been used as a cudgel against immigrants and the early labor movement.

Overseas in Europe, however, the Haymarket affair inspired the creation of May Day, as a major holiday honoring workers. As Dave Roediger and Franklin Rosemont describe in The Haymarket Scrapbook, May Day celebrations started in 1890 as a global show of workers’ solidarity. The first May Day in 1890 drew workers’ parades across Europe comparable in scale to those of the Great Upheaval. “[I]n Vienna it was a joyous holiday and in Berlin…there was a parade of 20,000. The British workers…had two thousand in a London parade” (Roediger and Rosemont 175). While May Day celebrations became a yearly occurrence in Europe, they were not seen often in America. The Haymarket affair thus led to two different results, with Europeans embracing more socialist ideas and greater workers’ rights, while Americans turned away from these views, instead using the Haymarket affair to suppress labor rights.

While it would be incorrect to say that the Haymarket affair killed the labor movement, it could be said that, around the time of the Haymarket bombing, America had reached a crossroads between greater workers’ rights, and a continuation of less regulated capitalism. One path may have led to a more socialist America, while the other led to the culture the U.S. has today. For better or worse, Haymarket greatly contributed to Americans’ negative view of socialism and other far-left ideologies that led to fundamental shifts in the future of the labor movement. In 1886, the same year that the Knights of Labor lost much of its relevance, the American Federation of Labor (“AFL”) was formed. It would become the most prominent labor organization in the first half of the next century. Compared to the relatively moderate Knights of Labor, the AFL were still far less radical, advocating for less aggressive labor reforms, opposing immigration from Eastern Europe, and barring membership by unskilled workers. In this way, the Haymarket affair created anti-immigrant hysteria that silenced early labor movements, and those emerging in its aftermath continued to support the anti-immigrant policies that Haymarket caused. This was the world that early 20th century readers of The Jungle inhabited, and explains why so many people at the time it was published tended to ignore the depiction of the harsh conditions faced by the Lithuanian immigrant protagonist and his family.

Works Cited

American Artisan. “The Eight Hour Movement.” Scientific American, vol. 54, no. 14, 3 Apr. 1886. JSTOR, Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Avrich, Paul. The Haymarket Tragedy. Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton UP, 1984.

DeMille, Anna George. “Henry George: Haymarket and Tariff Reform.” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 5, no. 4, July 1946, pp. 545-51. JSTOR, Accessed 20 Feb. 2024.

Gottesman, Ronald, and Richard Maxwell Brown. “Haymarket Square Riot.” Violence in America. Gale in Context: U.S. History, Accessed 29 Feb. 2024.

“Haymarket Bombing.” Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History, edited by Thomas Riggs, Gale, part of Cengage Group. Gale in Context: Biography, Accessed 23 Feb. 2024.

“Haymarket Riots.” Government, Politics and Protest: Essential Primary Sources, edited by K. Lee Lerner et al., Gale, 2006. Gale in Context: Biography, Accessed 23 Feb. 2024.

Keil, Hartmut. “The Impact of Haymarket on German-American Radicalism.” International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 29, spring 1986. JSTOR, Accessed 20 Feb. 2024.

Layson, Hana, and Leon Fink. The Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom. The Newberry DCC, Newberry Library, 14 May 2012, Accessed 12 Mar. 2024.

Nelson, Bruce C. “‘We Can’t Get Them to Do Aggressive Work’: Chicago’s Anarchists and the Eight-Hour Movement.” International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 29, spring 1986, pp. 1-15. JSTOR, Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

New York Times. “The Anarchists Cowed: Breaking up Their Haunts in Chicago. Forced to Seek Hiding Places – the Disorderly Element Thoroughly Frightened – The Strikes.” Famous Trials by Professor Douglas O. Linder. UMKC School of Law, Accessed 13 Mar. 2024. Originally published in The New York Times, 8 May 1886.

Parrish, Timothy. “Haymarket Square.” American History through Literature 1870-1920, by Parrish, edited by Tom Quirk and Gary Scharnhorst, Charles Schribner’s Sons, 2006. Gale in Context: U.S. History, Accessed 27 Feb. 2024.

Roediger, Dave, and Franklin Rosemont, editors. Haymarket Scrapbook. Chicago, Illinois, Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 1986.

Sampson, Robert D. “Governor John Peter Altgeld Pardons the Haymarket Prisoners.” Illinois Labor History Society, Accessed 25 Feb. 2024.

United States, U.S. Supreme Court (U.S.). United States v. Martin. Docket no. 94 U.S. 400, 1876. Justia, Accessed 6 Mar. 2024.

VandeCreek, Drew E. “Labor in Gilded Age Illinois.” Northern Illinois University Digital Library, Northern Illinois University, Accessed 5 Mar. 2024.

Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States. HarperCollins, 2003.