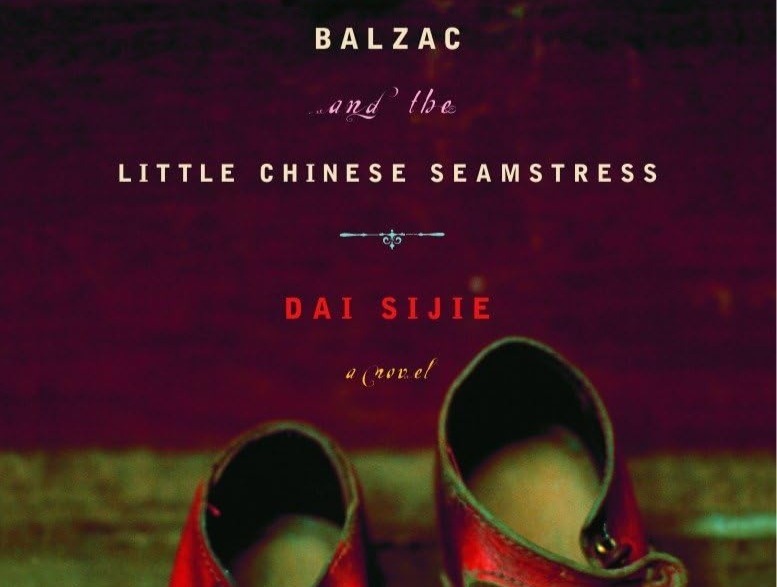

A note to the reader: while this argument will still be intelligible without having read Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, I highly encourage you to do so in order to have both greater context for this essay and to appreciate a work of literature I found to be highly enjoyable. This essay is a response to Ian McCall’s contention that the author, Dai Sijie, “conveys an image of Western superiority” through the book. With that in mind, I hope you enjoy the following essay.

We should understand Balzac and The Little Chinese Seamstress by understanding that the novel’s narration is not written to express the true thoughts of Dai Sijie, but rather to express the thoughts of the unnamed narrator. While the narrator may have an elitist and orientalist perspective upon the transformation of the little seamstress, that is not necessarily the author’s own personal beliefs. We should interpret Sijie’s book as a subtle commentary on the thoughts of his characters, using literary devices to point out the flaws in their reasoning, rather than uncritically assuming that the flawed perspective of the narrator is Dai Sijie’s own.

Balzac is a whimsical yet serious exploration of the Cultural Revolution in the People’s Republic of China. The narrator, and his friend Luo, are the sons of the intelligentsia. Banished to the countryside, they uncover a trove of banned books. After reading it to a peasant girl, they credit themselves for her intellectual development and eventual flight to the city.

Sijie uses literary techniques in order to distance himself from the thoughts of the characters. First, by using a character in the book, we understand that the narrator is not perfect or omniscient. By establishing that the book is about the thoughts of the main character rather than the true events that happen, Sijie emphasizes that the narration may be inaccurate, or at least biased. Second, when the narrator switches to being the seamstress, we learn that she is independent and “not like those young [ditzy] French girls” described by one of the books. (p. 144). Unlike why other people think she is retrieving his keys (implied on page 144: “why did I enjoy diving down to retrieve his key ring? I know what you’re getting at—you think I’m a silly dog”), she is doing it because she enjoys it. This establishes that while most of the narration suggests that she doesn’t have independent feelings, the most reliable account of her in the book (the only one that actually knows what she feels) suggests that she does act out of her own volition. This indicates to us that the narration about the little seamstress, especially when it suggests that she is not independent and instead influenced by other people, is unreliable.

Having established that the narration is often biased and inaccurate when it comes to describing the little seamstress, this helps us understand the rest of the narrative and the final quote. When the text implies she wants to go to the city because of the Balzacian education, (page 184: “she wants to go to the city…had learned one thing from Balzac”; page 180: “the ultimate pay-off of this…Balzacian education, was yet to come”) we should understand that as biased by the narrator’s own self-importance. This is not the objective reality of Sijie’s imagined world nor his own thoughts. This also applies to the rest of the text. On page 180, we see the narrator and his friend describe how they think they have saved the girl through literature, rather than this being an autonomous action of the girl herself. We can see the elitist opinion in how they describe how “the time we spend reading to her” and the “Balzacian re-education” as the impetus for her leaving, rather than the myriad of other factors that could have played a role. The narrator, to play up the importance of himself and Luo, make her flight and desire to live in the city a sole product of their own actions, rather than some independent desire of herself.

While the narration of Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress may be orientalist, that does not implicate the text itself. Dai Sijie uses literary techniques to imply the bias and inaccuracy of the narrator and narration. Therefore, when the text describes how the little seamstress was educated by French literature, we should understand that as the thoughts of the narrator rather than the opinions that Sijie or the book represent. While the book may initially appear orientalist, a close reading of the text reveals how it actually undermines the credibility of elitist narratives that appear in the text. Dai Sijie’s novel should be interpreted as a subtle critique of the narrator’s orientalism, rather than an expression of it.