Poverty is black ice.

— Naomi Ayala

You leave me sleeping in the dark. You kiss me and I stir,

fingers in your hair, eyes open, unseeing. You leave me asleep

every morning, commuting to the school in the city at sunrise.

The landlord’s driveway, a muddy creek, ices over hard after

the freezing rain clatters all night. Your feet fly up, your head

slamming the ground, an eclipse of the sun flooding your eyes.

You sleep under the car. No one knows how long you sleep.

You awake with a hundred ice picks stabbing your eardrums.

You awake, coat and hair soaked, and somehow drive to school.

You remember to turn left at the Smith & Wesson factory.

The other teachers lead you by the elbow to Mercy Hospital,

where you pause when the nurse asks your name, where you claim

your pain level is a four, and they slide you into the white coffin

of an MRI machine. You hold your breath. They film your brain.

Concussion: the word we use for the boxer plunging face-first

to the canvas after the uppercut blindsided him, not the teacher

commuting to school at sunrise in a Subaru Crosstrek. Yet, you would

drive, ears hammering as they hammer in the purgatory of the MRI.

A week before, Isabela came to you in the classroom and said:

Miss, I cannot sleep. Three days, I cannot sleep. Her boyfriend called

at 2 am, and she did not pick up. At 3 am, a single shot to the head

put him to sleep, and he will sleep forever, his body hidden beneath

a car in a parking lot on Maple Street, the cops, the television cameras,

the neighbors all gathering at the yellow-tape carnival of his corpse.

You said to Isabela: Take this journal. Write it down. You don’t have

to show me. You don’t have to show anyone. On the cover of the journal

you bought at the drugstore was the word: Dream. Isabela sat there

in your classroom, at your desk, pencil waving in furious circles.

By lunchtime, as her friends slapped each other, Isabela slept,

head on the desk, face pressed against the pages of the journal.

This is why I watch you sleep at 3 am, when the sleeping pills fail

to quell the strike meeting in my brain. This is why I say to you,

when you kiss me in my sleep: Don’t go. Don’t go. You have to go.

— Martin Espada, “Aubade with Concussion”

In “Aubade with Concussion,” Martin Espada depicts the unexceptional nature of violence in impoverished communities, and how that normalized violence still is braved by exceptional people in order to help others process their own trauma.

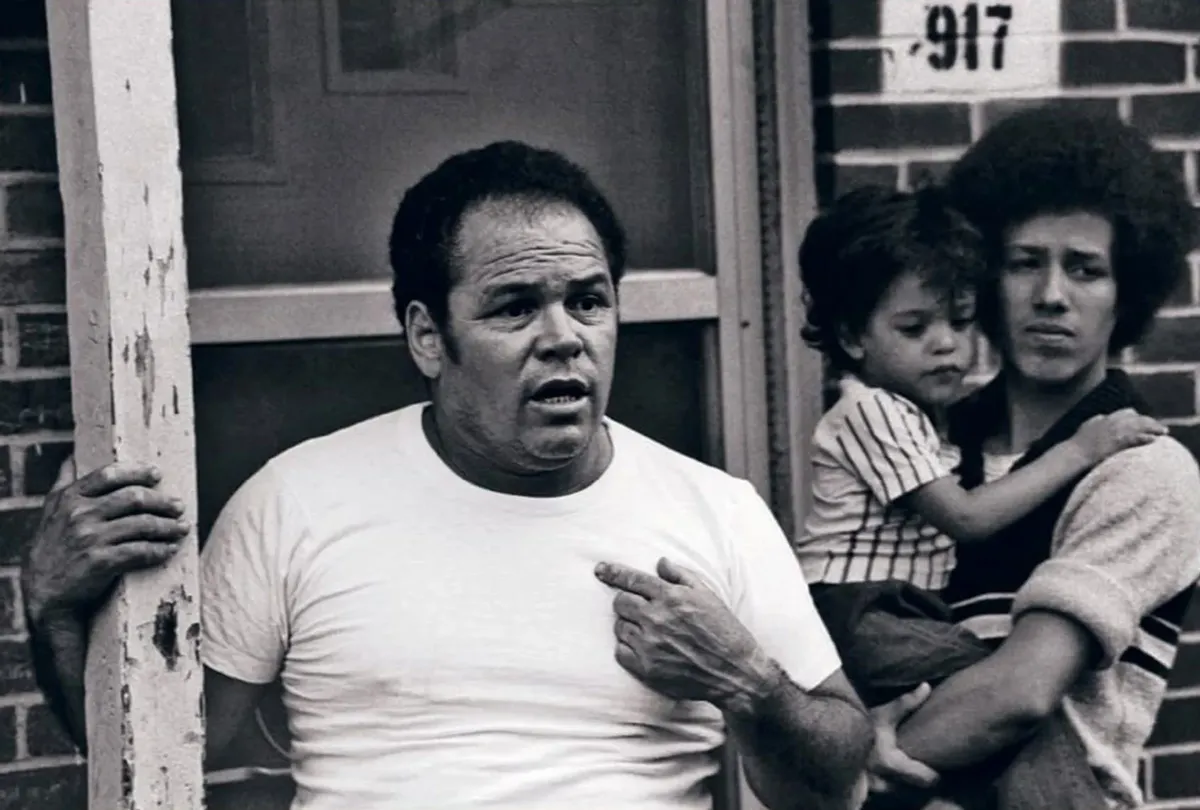

In the poem, the speaker describes how their lover, a high school teacher, has been concussed by slipping on the “poverty [which] is black ice”. Having to settle for a landlord’s “muddy creek” which “ices over hard”, the lover’s head goes “slamming into the ground”, causing a concussion. She is confused that this mishap has happened to her, a “teacher commuting to school” instead of “boxer plunging” from an uppercut. The teacher awakes, pained and dazed as if “a hundred ice picks [were] stabbing your eardrums”. Yet, despite this injury, she “somehow drives to school”. On the way, the teacher normalizes a Smith & Wesson factory, by only referring to it as a landmark (“turn left at the Smith & Wesson factory”), rather than as an exceptional factory of violence. Eventually, the teacher is persuaded by her colleagues to go to a hospital. While there, she continues to put on a brave face, saying that her “pain level is a four” despite her immense pain like the “ice picks stabbing”, as also mentioned earlier. Her pain continues to be borne, without complaint, even within the “purgatory” of a waiting room or MRI.

The poem then shifts, in time and subject, to a student, Isabela, helped by the speaker’s lover, in her role as a teacher. Unable to process her trauma, Isabela says “I cannot sleep [for] three days”. Like the speaker earlier, Isabela does not awake when her partner calls. He dies that night, with a murder through “a single shot to the head” as she slumbers on. The teacher helps Isabela process her anguish by giving the student a journal and an instruction to dream, to not fixate on the distress she has recently experienced. She also instructs Isabela that she doesn’t “have to show anyone” the contents of her journal and experience, just how the teacher herself resists revealing her concussion to her peers. Isabela is enraptured by her journal, and through writing “furiously”, manages to sleep, having processed her trauma.

Espada uses poetic devices to suggest the answer to some specific yet ambiguous subclaims within the poem, such as how the speaker is the teacher’s lover. Another uncertain subclaim is the process of Isabela’s partner’s death. We think that it was most likely murder. First, instead of being shot by himself, the poem suggests that the bullet has shot at him (“a single shot to the head”), a description that deemphasizes the partner’s autonomy in the matter. Second, if the death was a random suicide, it would be unusual to have “the television cameras…all gathering at the yellow-tape carnival of his corpse”. There are also some symbolic devices whose meaning can be derived, but less specifically. Sleep, for example, is used to represent unconsciousness (“head slamming the ground…you sleep under the car”), death (“shot to the head…he will sleep forever”), literal sleep (“three days, I cannot sleep”) and the successful processing of trauma (“Isabela slept”/“the sleeping pills fail”). More specifically, the two incidents of sleep associated with literal violence are described as under the car (“you sleep under the car” / “he will sleep…beneath a car”). The speaker is the lover of the high school teacher, for two reasons. First, a child old enough to use words like “aubade” or “purgatory” is rare, doubly so one young enough to still be kissed every morning before the parent leaves. Second, it sets up a clear parallel between the speaker/teacher and student/partner relationships. The speaker has a dialectical attitude towards the teacher working to help their student, saying to the subject “don’t go. You have to go”. Here, the speaker does not want to leave but recognizes that they have to go in order to help those who need it most, even if it is dangerous.

“Aubade with Concussion” has themes that are relevant for our understanding of both our world and Espada’s other poems. Like “Death Rides the Elevator” and “The Stoplight at the Corner Where Somebody Had to Die”, the poem describes literal death and trauma as symbols, in order to make a broader point. “Aubade with Concussion” also deals with themes of love and partnership between people, which is a major theme throughout “Why I Wait for the Soggy Tarantula of Spinach” and Part III of “Floaters”, the book where “Aubade with Concussion” was published. Espada describes his own experience in seeing his partner build resilience at the cost of herself, while intending to demonstrate his own experiences in processing the anguish associated with loving such a person. The poem elicits sympathy and understanding for those who sacrifice themselves in order to help heal the pain of others. In that way, it is an aubade to perseverance, a love letter to that value which does not stir as a result of Espada’s reference to it.