Guns, Germs and Steel: Diamond in the Rough

He is covered by nearly every world history class at New Trier. In 2001, Cornell put his book on the mandatory freshman reading list (Jaschik). Yet, as far as Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel pervades, it met unforgiving backlash from anthropologists worldwide. Where did his synthesis of agriculture and imperialism so seriously fail? What legacy does a framework of environmental determinism leave on future interpretations of colonialism?

Diamond’s Argument

In episode 1 of his PBS special, a visual depiction of Guns, Diamond begins with Yali, a local farmer on the island of Papua New Guinea. The text centers around Yali’s question: “Why is it that you white people developed so much cargo, but we black people had little cargo of our own?” Diamond justifies Europe’s rise as a colonial power and the subsequent disparity in wealth distribution with a series of geographical flukes and accidents. He frames his work as a rebuttal to racial determinism, claiming that the inequality had “little to do with ingenuity or individual skill,” and that instead, “the blueprint for global inequality lies within the land itself.” Specifically, he cites that the Eurasian countries which farmed and domesticated beasts of burden could drift away from a hunter-gatherer society and into one which exhibits specialized skills. Additionally, the lucky exposure to beasts of burden granted Europeans immunity to diseases otherwise deadly to people in Africa and South America. Lastly, because Eurasia’s trade routes crossed similar latitudes, farming technologies could easily adapt to the similar climates. With this litany of historical anecdotes, it comes as no surprise how his “blueprint for global inequality” succeeded in convincing so many.

Could, should, or would have?

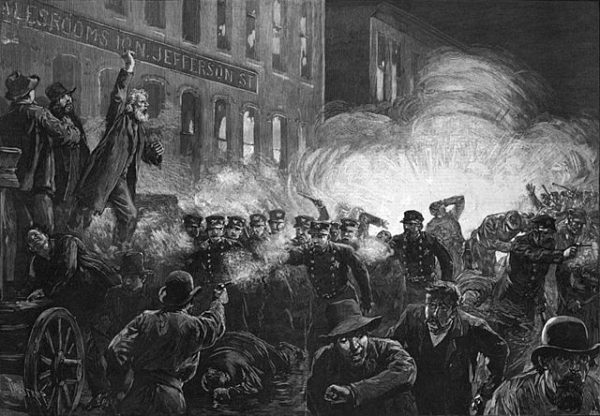

In the second episode, Diamond claims that “it was these agents of conquest that allowed 168 Spanish conquistadors to defeat an Imperial Inca army of 80,000.” Within Diamond’s closed system of agricultural determinism, these pieces fit without flaw. Stepping back, however, it exists beyond reason that an army of 168 could possibly defeat that of 80,000 chiefly based on the lucky difference between “horses vs llamas.” Just because the horses could have made the difference does not mean they likely would have. Diamond fails to credit the aid of native armies in Pizarro’s conquest, driven by their own motives and acting on their own choices to topple local imperial rule (Antrosio). Displaying agricultural causation and the collapse of civilizations in a vacuum excludes the context of these other causation theories. His theory here incorrectly portrays the Spaniards’ luck as the greatest determining factor in their conquest. Studying conquest through this historical interpretation still upholds the western exceptionalism hidden within the racial determinist arguments Diamond appears to refute.

Even granted occasions of true ‘geographic luck’, imperialism is ultimately still a choice. The mere possession of ‘guns, germs, and steel’ does not fate conquest as an inevitability and therefore justify its pursuit. The natives died from smallpox not because they lost the immunity lottery, they died because colonizers made a deliberate choice to distribute smallpox blankets taken from sick wards (Antrosio). Just because the Spaniards could have slayed the native population, does not mean they should have. Yet, Diamond’s use of rhetoric such as ‘luck’ and ‘allowed’ sterilizes the violence as the expected outcome of excess possession or advantage. The portrayal of action without agency dilutes Pizarro’s responsibility in these crimes. So long as Diamond’s environmental determinism depicts the perpetrators of inequality as simply ‘lucky’ instead of brutal, it remains an impossibility to hold them fully accountable.

How should historians actually answer Yali’s question?

Perhaps Yali’s question of cargo never really asked for a history of environmental causations. Anthropologists Frederick Errington and Deborah Gewertz suggest in Yali’s Question: Sugar, Culture, and History that he really wondered about “the reluctance, if not refusal of many whites to recognize their full humanness-to make blacks and whites equal players in the same history” (Antrosio). Thus, to truly answer Yali’s question, one must include the true nature of agency and responsibility possessed by both colonizer and native.

Works Cited

Antrosio, Jason, 2011. “Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond: Against History.” Living Anthropologically website, https://www.livinganthropologically.com/archaeology/guns-germs-and-steel-jared-diamond/. First posted 7 July 2011. Last updated 7 June 2020.

David Correia , Capitalism Nature Socialism (2013): F**k Jared Diamond, Capitalism Nature Socialism, DOI: 10.1080/10455752.2013.846490

“Guns Germs & Steel: The Show. Episode One.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/gunsgermssteel/show/episode1.html#:~:text=There%2C%20in%201974%2C%20a%20local,the%20roots%20of%20global%20inequality.

“Guns Germs & Steel: The Show. Episode Two.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/gunsgermssteel/show/episode1.html#:~:text=There%2C%20in%201974%2C%20a%20local,the%20roots%20of%20global%20inequality.

Jaschik, Scott. “’Guns, Germs, and Steel’ Reconsidered.” Inside Higher Ed, 3 Aug. 2005, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2005/08/03/guns-germs-and-steel-reconsidered.

Teddy

May 27, 2022 at 7:52 am

An excellent and through deconstruction