Before Yellowstone: It Was Never Just Empty Land

Prior to the migration of European settlers to the United States, and Yellowstone’s formation as a national park in 1872, Yellowstone contained many flourishing Native American tribes that coexisted in a unique ecosystem. Bison, deer, and bighorn sheep roamed the land, providing a sustainable food source and materials to build homes and clothing. Fish swam through clear rivers and streams, while geysers blasted scalding hot water high into the air. Although many of these tribes were nomadic, and the amount of time each tribe spent in Yellowstone differed greatly, this unique environment served as a perfect location for more than two dozen different tribes over the last 11,000 years (MacDonald 368).

Yellowstone’s many geysers and unique stone formations provided an important cultural service for Native Americans. According to “Historic Tribes,” an online archeological archive of Yellowstone, many tribes, “used the thermal waters for religious and medicinal purposes.” Specifically, some tribes believed that the power of these locations could allow them to communicate with those who had previously passed away, and tribes would travel long distances to consult with those spirits before making meaningful or important decisions (MacDonald 443). Other times, Native leaders would take a group on a spirit journey, traveling high into the mountains and peaks of Yellowstone. There, they would construct circles of stone a few feet high and long enough so that someone could lie down inside the circle, using it as a makeshift shelter as they partook in their journey. The member of the tribe going on the spirit journey would then refrain from eating or drinking until they received the answers they were looking for (2322).

These traditions contrasted greatly with ways early European settlers practiced religion at the time. In contrast to Native traditions, many of the Europeans who settled around Yellowstone worshipped in a church and communicated with a priest. Thus, many settlers were ignorant of Native forms of spirituality, some going so far as to suggest that Native tribes avoided Yellowstone because the tribes believed malevolent spirits resided in geysers. (Grant). While this was wholly inaccurate, many settlers would not communicate with the Natives who lived in Yellowstone, viewing them as savages who would never be able to speak with them intelligently. It becomes clear to any researcher that this stubbornness and discrimination then created a self-perpetuating cycle of misinformation about tribal spiritual practices for decades to come. Settlers would form beliefs around misinformation that thrived in a culture of exclusivity. Greater communication between settlers and Native Americans may have been the one thing that could have clarified misconceptions. While this may appear obvious looking back from an impartial perspective, in the eyes of the settlers who at the time advocated for Yellowstone to be taken from Native control and turned into a national park, their actions were completely justified since, in their minds, the Native tribes were afraid to be in the park in the first place.

Contrary to the ethnocentric views of European settlers that diminished the cultural sophistication of Native Americans, Yellowstone contains evidence of complex tools, art, and pottery made by tribes. Andrew Geiger, a British journalist for The Smithsonian Magazine, described some examples of the carefully made weapons he has found in Yellowstone, writing, “A 10,000-year-old hunting spear tip made of obsidian. It was produced by knapping, using hard rocks and antlers to break off flakes.” Here, we can see that tribes used the resources of Yellowstone to their advantage, cleverly crafting a spear tip out of obsidian. Considering the limited resources and tools Native tribes had access to, it is apparent how resourceful many of the Native people in Yellowstone were thousands of years ago. In addition to creating powerful and complex hunting tools, Native tribes created art in Yellowstone that has lasted thousands of years. Huge “petroglyphs,” or images carved into stone, have been found on mountainsides in Yellowstone (MacDonald 2601). The images are mostly of spirits or animals found within the park, although much about them remains unknown. However, it doesn’t take a team of researchers to see just how much work was put into the art around Yellowstone. The creators of the petroglyphs carved the images into the stone at an angle, often in direct sunlight. In addition to the physically difficult nature of the work, the work required careful planning because of its sheer size (554).

The migrating patterns of the tribes also reveals the complexity of tribal organizations. Tribes that inhabited Yellowstone often migrated, splitting their time between multiple locations. Instead of choosing one location to live all year long, tribes would strategically move to where food would be plentiful and easy to hunt (Grant). Most of the food acquired was through hunting, not farming, which allowed much more freedom in movement. To facilitate this, tribes would construct complex temporary forms of housing, not wanting to waste valuable materials on a home that may last a few months. “Historic Tribes” describes one such home, called a Wickiup, saying, “Wickiups provided temporary shelter for some Native Americans while they were in Yellowstone. No authentic, standing wickiups are known to remain in the park.” Because of their temporary nature, very little archaeological evidence of these homes exists today. (MacDonald 532). Most of what we know is provided from the descendants of the tribes who passed on the information through oral histories. However, when settlers arrived and found these temporary structures made of animal hides and branches, the structures seemed bizarre. Settlers couldn’t comprehend that what they were seeing was someone’s home. The skins and sticks were a polar opposite to the stronger, more permanent materials settlers used. Years later, when relegating tribes to different areas via reservations, settlers ignored the nomadic nature of some Native American tribes, opting instead to confine them to specific locations.

Prior to the nationalization of Yellowstone Park, for thousands of years Yellowstone was a flourishing park, providing a home for dozens of unique tribes. In order to truly examine how the government managed the different tribes within Yellowstone, we have to examine instances when the government engaged with tribes. Specifically, from the park’s creation in 1872 to the current day, the government has tried many different strategies of engaging with tribes, from outright ignoring the existence of Native Americans within Yellowstone, to creating advisory and consultation boards composed of Native people (Trerise et al.). I would argue that none of the strategies the United States has employed are successful or acceptable. Until the day when the United States recognizes the full weight of Native claims on Yellowstone and grants them a meaningful role, the government will have not done nearly enough.

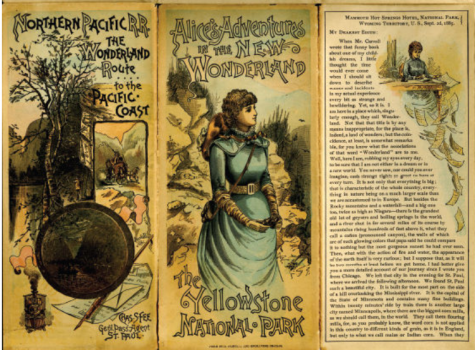

Ignoring the sovereign rights of these tribes fit the self-serving narrative the United States wanted to create. When Yellowstone Park was first created, the burgeoning National Park Service did everything in its power to downplay and deny the existence of Native tribes within the park. Early advertisements depict the park as a pristine and empty section of land, untouched by any sort of society. MacDonald displays in his book Before Yellowstone: Native American Archaeology in the National Parks one such advertisement, a pamphlet aimed to encourage tourism to Yellowstone. It compares Yellowstone to Alice’s Wonderland, calling the park, “the New Wonderland,” a whimsical world meant to be observed and admired, but never actually lived in. Of course, this purposely leaves out the dozens of tribes that had spent thousands of years on the land.

This theme of emptiness shows up again and again in settler literature and media. Danielle Mamers, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania describes this phenomenon in her paper, “‘Last of the Buffalo’: Bison Extermination, Early Conservation, and Visual Records of Settler Colonization in the North American West.” In this, she examines a book of photography published 1907 that purposely left out Native people when taking landscape photos. Mamers remarks, “These landscapes depict a simplified version of the places … naturalizing both settler claims to presence and Indigenous erasure. Complex histories of Indigenous resistance, colonial legal machinations, and the radical loss of species and multispecies relations due to extermination are left out of Luxton’s frame.” Here, we see again the erasure of Native existence in favor of a narrative that depicts pre-settler America as empty and open for the taking. We are able to infer that this narrative helped relieve the guilt of settlers – after all, it’s hard to enjoy the beauty of Yellowstone if you know its dark history of colonialism. This strategy would not continue forever. As more Americans became aware of Native Americans during the twentieth century, the government was forced to adapt its strategy of engagement with tribes.

During the mid-twentieth century, the government took its first steps towards recognizing the existence of Native tribes within Yellowstone. The National Park Service took several steps that, while initially seemed conciliatory, upon further review were equally as paternalistic as removing Native people from Yellowstone. “Indigenous Homelands in Yellowstone National Park,” a collection of data on the history of Yellowstone created by the University of British Columbia, describes these practices, saying, “[Native Americans] were forced onto reserves prohibiting hunting and gathering in the park. The Indigenous people’s way of living, such as burning and hunting, did not line up with the idea of preservation.” We see that Native Americans were eventually granted access by the United States to re-enter Yellowstone park. However, this re-entry was entirely on the United States’ terms since the different tribes of Yellowstone had no bargaining power to. Thus, the life they were given within Yellowstone was a poor imitation of their traditional ways of life. They were banned from hunting bison, a crucial food source, and were extremely limited in what other animals they could hunt, forcing them to find food from other sources. Additionally, the reserves of land kept them tied to one spot for the entire year, unlike the nomadic life that many tribes had preferred in the past. Since these reservations were formalized by official proceedings from the Department of Interior, they carried a legitimacy previous interactions between the government and tribes had not. However, it’s important not to mistake this legitimacy for actual progress. Native people were forced to cohere to western ideas of species preservation and living, including limits on hunting or travel. Thus, many Natives were forced to choose between living a shadow of their previous lives or assimilating into western society.

Interactions between the United States and tribal governments look much different today. Formal mechanisms such as the National Congress of American Indians exist to bargain with the federal government for better conditions for Native Americans. Specifically, Yellowstone Park officials began working with tribes in a professional capacity in order to try to incorporate more indigenous presence into the park. Dennis Zotigh, a journalist for the Smithsonian Magazine specializing in Native American history writes, “…today the National Park Service works with Native partners to preserve archaeological, historic, and natural sites. Collaborations include the Tribal Preservation Program, American Indian Liaison Office, and Ethnography Program.” The litany of programs described is an obvious improvement from the past. When considering how afraid the United States was of even acknowledging Native American presence in the nineteenth century, it seems like a miracle that these partnerships would ever exist. While there are plenty of success stories, the partnership that exists now still leaves much of the power in the hands of the National Park Service. For example, in 2018, the Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Association, a collection of members from sixteen different Sioux tribes, petitioned the National Park Service to rename two landmarks within Yellowstone (Begay). Mount Doane and Hayden Valley, both landmarks within Yellowstone, are named after settlers Native advocates saw as complicit in the genocide of Native Americans. Both Doane and Hayden advocated for the forced assimilation of Native Americans and the eradication of all Native culture. In the two years that passed since the Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Association petitioned the government, not much has changed. Both landmarks are still referred to by their original names on government maps and websites, and much of the news coverage has died down. While the move to rename both areas was popular with Native Americans, very little has been done within the government to actualize these demands.

After analyzing the relationship between the United States and Native Americans over Yellowstone, it becomes clear that the government is steadfast in its denial of Native tribes’ sovereignty over historically Native land. Although the way that the United States engages with tribes changed over the last century, the fact remains that the government benefits from the removal of Native culture from Yellowstone. Thus, the question becomes one of how to effectuate real change.

Looking toward modern Native American politicians and political organizers, we can examine the strategies that are being utilized today to engage with the United States. Native American leaders are emerging as powerful political figures. While politicians like Deb Haaland, a Laguna Pueblo tribal citizen and recently confirmed head of the Department of Interior, represent a desire to actualize change directly via the government, a litany of grassroots movements exist on a local level that push for things like land repatriation and increased Native sovereignty. Together, grassroots movements and powerful politicians have created a strategy that has benefited Native Americans.

Native Americans have used traditional methods, such as running for office and petitioning their representatives to achieve change. With Deb Haaland’s recent confirmation, she became the first Native American to hold a cabinet position (Fahys). In her new position, Haaland will be responsible for 413,000,000 acres of land, in addition to handling most federal interactions with Native tribes. Haaland has already been vocal about wanting to support Native rights, saying it’s a top priority for her. Her record includes vocally protesting the Keystone XL Pipeline, supporting the Green New Deal, and advocating for incorporating Native voices into national climate policy. More broadly, Haaland represents a shift towards a more cooperative relationship between the federal government and tribal governments. Although Haaland is still in her first few weeks of office, many Native tribes have signaled they’re hopeful about the future of the Department of Interior. Julian Brave Noisecat, a member of the Canim Lake Band Tsq’escen and descendant of the Lil’Wat Nation of Mount Currie who spent years advocating for incorporating Native Americans into public policy, described this optimism, saying, “With Haaland’s appointment, we have turned a page—not because the insiders wanted it, but because the people fought for it.” More than a symbolic victory or ineffective advisory role, her appointment is perceived by Native political advocates as a real position of power within the government. Although Haaland will certainly face pushback, her confirmation is something that can’t be easily revoked or altered, creating a lasting mechanism by which Native people can actualize change. However, it’s important to note that this all exists solely because of Native organizing – not the government – as Noisecat indicates by saying, “people fought for it.” Haaland proves not only the need to elevate Native people within the government but to support Native-led organized movements and advocacy.

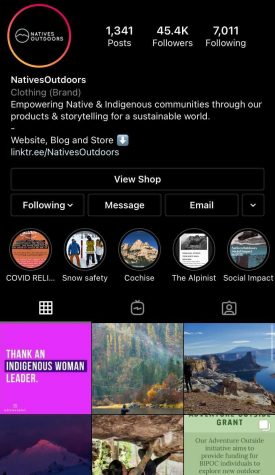

In addition to incorporating Native people into the government in order to create tangible progress, grassroots movements have been incredibly effective in bringing awareness to the history of National Parks, such as Yellowstone. One of the biggest challenges in increasing the sovereignty of Native Americans within Yellowstone has been public ignorance, which, in turn, rewards federal apathy towards Native people. Different Native advocates have made efforts to create awareness. Jason Begay, a professor at the University of Montana School of Journalism who specializes in Native American rights, described one such advocacy group, writing, “The organization NativesOutdoors is … an Instagram account with [45,000] followers. The founder, Len Necefer, of the Navajo tribe, has been working for years to encourage Instagrammers to use original tribal names in the app’s geotagging feature instead of Americanized names.” By using original tribal names, people can simultaneously learn more about Native culture and history while not supporting the Americanized names for landmarks, many of which are named after settlers complicit in the erasure of Native people. While it’s hard to gauge how successful grassroots movements are, the eighteen thousand people in concomitance with the account demonstrate the reach of Indigenous grassroots activism. For an issue as niche as the naming of different landmarks within Yellowstone, any additional person educated counts. That way, when Native groups petition the government to see landmarks named after colonialists renamed, there’s a broad base of support behind them that can put pressure on lawmakers.

Achieving progress and recognition for the Native tribes within Yellowstone isn’t easy, especially when facing centuries of mismanagement and ignorance. The United States has repeatedly treated Native tribes as inferior, granting them little, if any, meaningful role in the management of Yellowstone Park. While tribal consultation groups exist, they’re often marginalized, left in a strange limbo where their demands haven’t been granted or denied. The most meaningful ways progress has been achieved have been by directly placing Native people in positions of power, although even that isn’t a perfect solution. People like Deb Haaland and Len Necefer are cause for optimism and represent a shift towards Native people having more power. But there is still much to be done, both inside Yellowstone Park, and everywhere else, and for activists like Professor Begay, the road ahead is daunting.

Works Cited

Begay, Jason. “Native Americans Seek to Rename Yellowstone Peak Honoring Massacre Perpetrator.” The Guardian, 5 July 2018, www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/jul/05/native-americans-yellowstone-mountain-renaming. Accessed 9 Feb. 2021.

Buss, W. American Bisons Grazing in Pasture. 5 May 2016. Britannica Image Quest, quest.eb.com/search/126_3754901/1/126_3754901/cite. Accessed 25 Feb. 2021.

“Conservation and Native American Representatives Call on Norton to Immediately Halt Killing of Yellowstone Buffalo.” U.S. Newswire, 12 Mar. 2003. ProQuest News and Magazines, newtrier.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.newtrier.idm.oclc.org/wire-feeds/conservation-native-american-representatives-call/docview/451054745/se-2?accountid=36487. Accessed 4 Feb. 2021.

Fahys, Judy. “What’s on Interior’s To-Do List? A Full Plate of Public Lands Issues—and Trump Rollbacks—for Deb Haaland.” Inside Climate News, 22 Feb. 2021, insideclimatenews.org/news/22022021/whats-on-interiors-to-do-list-a-full-plate-of-public-lands-issues-and-trump-rollbacks-for-deb-haaland/. Accessed 23 Feb. 2021.

Grant, Richard. “The Lost History of Yellowstone.” Smithsonian Magazine, Jan.-Feb. 2021, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/lost-history-yellowstone-180976518/. Accessed 16 Feb. 2021.

“Historic Tribes.” National Park Service, U.S. Department of Interior, 18 Sept. 2019, www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/historic-tribes.htm. Accessed 23 Feb. 2021.

Johnson, Benjamin Herber. “The Dark Side of American Environmentalism.” Reviews in American History, vol. 29, no. 2, June 2001, pp. 215-21. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30031221.

MacDonald, Douglass H. Before Yellowstone: Native American Archeology in the National Park. E-book, U of Washington P, 2018.

Mamers, Danielle Taschereau. “‘Last of the Buffalo’: Bison Extermination, Early Conservation, and Visual Records of Settler Colonization in the North American West.” Settler Colonial Studies, vol. 10, no. 1, 2020, pp. 126-47, doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2019.1677134. Accessed 9 Feb. 2021.

NoiseCat, Julian Brave. “Deb Haaland’s Cabinet Nomination Is a Triumph for Native Americans.” The Nation, 8 Jan. 2021, www.thenation.com/article/politics/haaland-native-american-biden/. Accessed 8 Mar. 2021.

Torbit, Stephen C. “A Commentary on Bison and Cultural Restoration: Partnership Between the National Wildlife Federation and the Intertribal Bison Cooperative.” Great Plains Research, vol. 11, no. 1, Spring 2001, pp. 175-82. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23775646. Accessed 16 Feb. 2021.

Trerise, Bridget, et al. Indigenous Homelands in Yellowstone National Park. U of British Columbia, 2018. Open Case Studies, cases.open.ubc.ca/indigenous-homelands-in-yellowstone-national-park/. Accessed 9 Feb. 2021. I found the date using carbon dating the web. Although it’s been reliable every time I’ve used it, I know it’s not the most reliable method, so I can just leave the date empty instead. However, I couldn’t find the official date this was published on the website, so I thought this was the next best thing.

Vernizzi, Emily A. The Establishment of the United States National Parks and the Eviction of Indigenous People. Edited by Benjamin F. Timms, California Polytechnic State University, Spring 2011, digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1070&context=socssp. Accessed 16 Feb. 2021.

Zotigh, Dennis. “How Native Americans Bring Depth of Understanding to the Nation’s National Parks.” Smithsonian Magazine, 25 Aug. 2020, www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-american-indian/2020/08/25/natives-interpreting-national-parks/. Accessed 16 Feb. 2021.